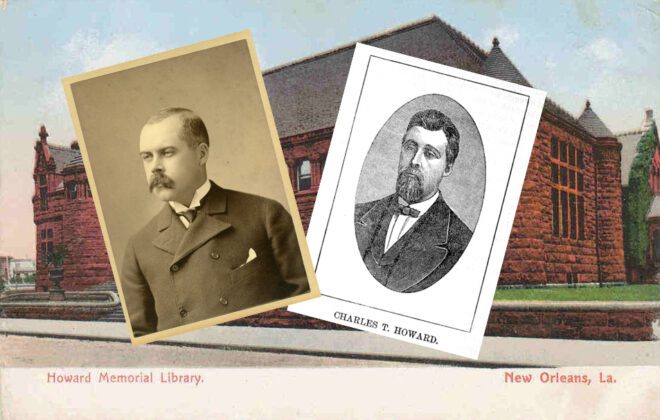

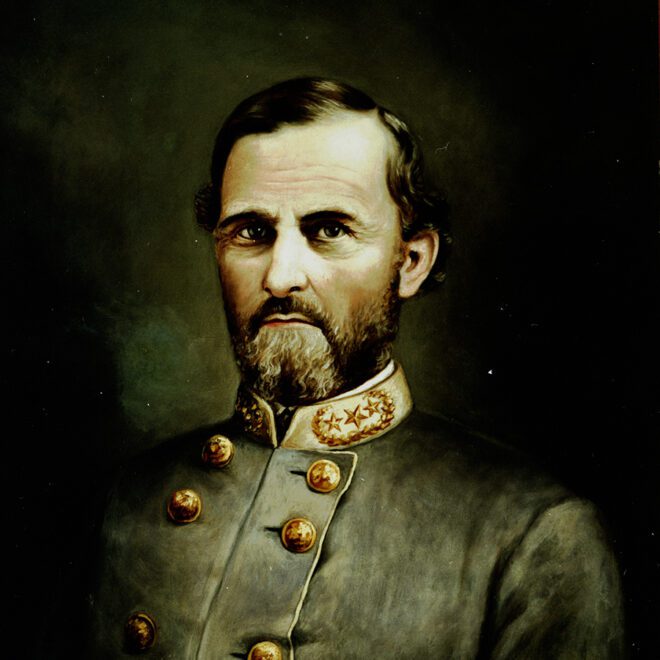

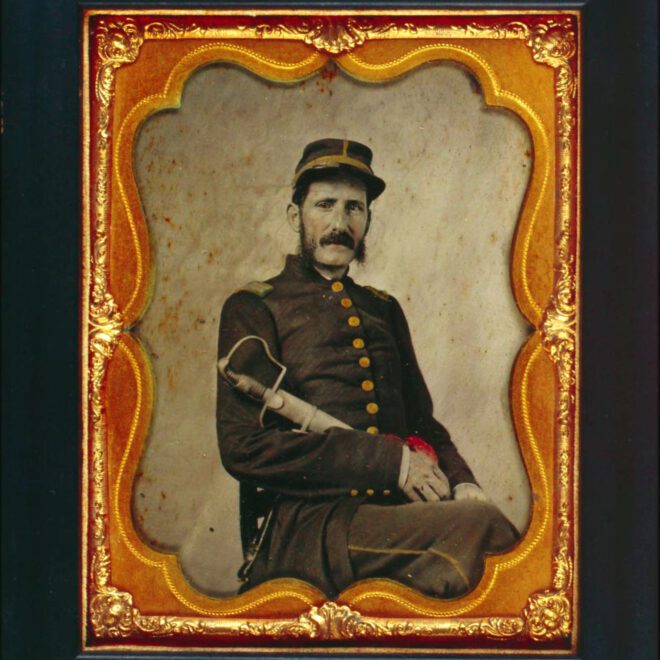

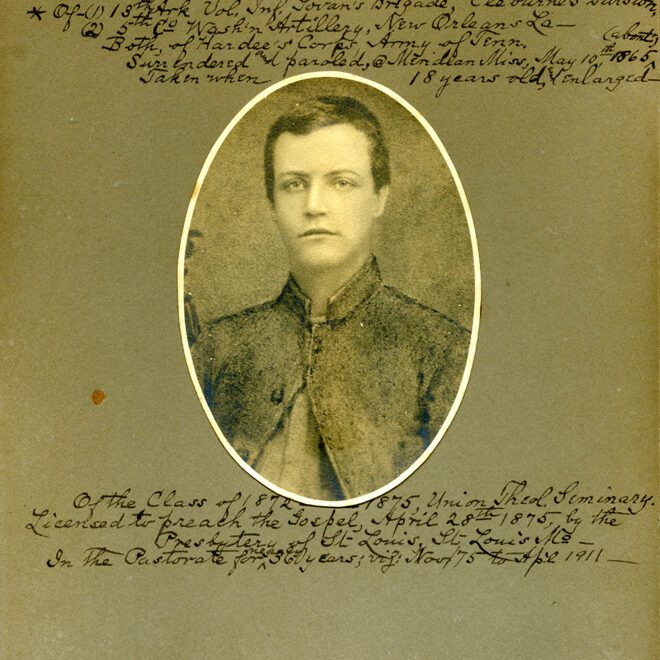

In the twenty years following the end of the Civil War, the Confederate Veterans organizations of New Orleans sought a common place with which to “unite” and house their growing collections of documents and relics relating to the conflict. In 1889, these Confederate Veterans formed the Louisiana Historical Association and chose the newly constructed Howard (now Patrick Taylor) Library on Lee Circle. A small “alcove” within the Library became a repository for war relics, documents, and other artifacts of the Civil War period until the collection threatened to outgrow the space. It was at this point, that Frank T. Howard, a local philanthropist, and benefactor of the Library, stepped in. Mr. Howard wished to construct an Annex to the library in honor of his New York born father Charles, who fought in the Confederate army during the Civil War. The younger Howard was active in the ill-fated Louisiana Lottery of the 1880’s and believed that he needed to honor the sacrifice of the Confederate soldiers who, like his father, gave their all for the Confederacy. Construction of the “Howard Annex” as Memorial Hall was referred to, was completed in December of 1890. The exterior structure is Romanesque in style and was designed by the architectural firm of Sully and Toledano of New Orleans. The interior main hall is constructed of rich Louisiana Cypress wood and features seven main trusses that transverse the room overhead while a variety of glass exhibit cases surround the room at the floor level. A gasolier provided light from each beam.

The Confederate Memorial Hall of New Orleans opened its doors on January 8, 1891 to the pomp and ceremony. The event featured notable speakers from the many Confederate veteran organizations along with religious and political oratory. The organizations represented were the Army of Northern Virginia Association, Army of Tennessee Association, Washington Artillery, the Association of Confederate States Cavalry, and of course the Howard Library Association.